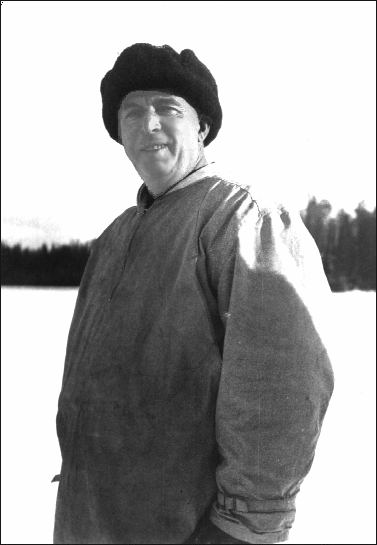

Nelson Spiers - c.1936

Nelson Spiers - c.1936EXCERPTS FROM THE JOURNAL OF NELSON SPIERS 1888-1963

With the kind permission of his daughter Eleanor Randell

Something that my father and grandfather never did before they passed away was to leave a history of their pioneer days, of hardships they encountered trying to make a home for their wives and children, of the early days of lumbering on the Ottawa River and the big rafts of hewn square timbers. It is known that my father hewed the biggest stick of square birch that ever left Canada for England. If I am spared long enough I intend to write a history of my life, varied as it has been. I have made mistakes, we all do. I hope that God will forgive me for the mistakes that I have made.

My Greatgrandfather came from Cardiff in Wales (1). He settled in or near Ottawa and as far as I know, followed lumbering and the sawmills. My grandfather came from Arnprior with his family to Muskoka (in 1878). It was a great white pine lumbering district in those days. He cleared up a very nice farm and raised a large family - 6 girls and 3 boys. My grandfather Spiers was very religious (Church of England). We used to go there sometimes to spend the night and it was prayers at night and prayers before breakfast with all the family in one group.

I was born in the Province of Ontario in the District of Muskoka, Stisted Twp., on the 8th day of December, 1888. My father's name was Thomas Spiers and my mother was Sarah Mawhinney. My mother's people were Irish. they came north from Kentucky and settled near Woodstock, Ontario, then moved on to Muskoka. My grandfather, William Mawhinney, came from Cork in Ireland. I have often wondered how he ever was the strong Orangeman that he was; they must have chased him out of the south of Ireland. There were eight in the Mawhinney family, 4 boys and 4 girls - Joe, Jack, Alex, Charlie, Sarah, Tilly, Binney and Agnes. My father and mother were married by the English Church minister at my grandfather's home on the farm about 7 miles from Huntsville. My grandmother gave my mother a cow to start out with.

My first recollection is of the farm that my father had cleared. We had a frame house and a large hip-roof frame barn with stables underneath. In the year 1900 my father built a brick house and I can remember trying to throw the bricks up onto the scaffold for the brick layers. Mr. William Head was the carpenter contractor and the brickwork was done by a contractor from Huntsville. I remember when I was small that we, and the other Spiers, would all go to grandfather Spiers' for Christmas. Then we would go to the Mawhinneys for New Years. Christmas was very religious but New Years at an Irishman's home was something else. I can remember them dancing and whooping it up until daylight. We were always put upstairs to bed but, like all kids, we used to listen to what was going on.

In the summer my father worked the farm and in the winter he would take a team of horses (some winters, 2 teams) and go to work in the lumber camps. I would help my mother look after the stock. The winters in those days were very long and cold and the snow very deep. When my father returned home with the teams in the spring, he would have to leave the sleighs out at that road and single file the horses to get them through the snow to the barn. We lived about 1/8 mile off the government road and about 8 miles from Huntsville. During the time my father was away, usually about 2 months, we would not get out to town, as most farmers did in those days, but there was always lots of supplies to see the family through the winter. We used to go to church at home, but only before father went to the camps would he get the family on their knees and pray that everything would be all right during his absence. At that time our neighbours on the adjoining farms were the Scotts, Wallingtons, Brays, Stahls, Proudfoots, Madills, Howards, Fetterlys, Darlings, Tuppers, Goldethorpes, Shays and Smiths.

I went to school at the little red schoolhouse near the railroad tracks at the corner of four townships and a tough bunch of students it was. A woman teacher was out of the question. One time five of us big boys took the teacher, a Mr. Keho, outside and rolled him in a mud puddle. There was hell to pay about that and we were all suspended for a month. One boy, Ernest Fetterly, was the leader and he was suspended for good. My punishment at home was hoeing potatoes and field roots for the whole month. I remember saying to myself, "As soon as I get a little older I'm going to run away and go to work in the camps or on the boats." At that stage in life a boy does not know when he is well off.

When I was 17 I did nearly all the work on the farm that summer. My father was sawyer in Darling's sawmill, but he was home for the haying and harvest. We also had a Barnardo Boy who was 14 and he helped a lot after school and on Saturdays. That winter I worked in the Muskoka Wood Mfg. Co. camp up on the Black River at the headwaters of Vernon Lake. The next winter I went on a white pine cut in Algonquin Park for the Huntsville Lumber Co. I went in the 1st of Novemeber to Hector Scott's camp and stayed until the drive on the Big East River was finished on the 20th of June. That was my first experience in a real lumber camp; men were men in those days. We would work hard for six days a week and on Saturday night there would be singing, step dancing and the usual poker game. On Sunday no one was ever allowed to grind an axe, shoe a horse or do any other work. Those old lumber camp foremen may of been tough men but they had standards they lived by - Sunday was to be a day of rest.

In the spring of 1911 I went to Porcupine where the gold camp was just opening up. I started to work at the Vipond Mines and operated a steam-piston drill set up on a tripod. When they started to sink a shaft, I worked in that down to 70 feet with a steam-piston machine. It was awfully hot. The big Porcupine fire came the 11th of July, 1911 and swept the country. We, of the Vipond, went over to a small lake at Hillinger, between the mine and where the town of Timmins was eventually built. After the fire went past we went down to the Moneta where they had not been burned out and stayed there that night. The next morning we walked to South Porcupine; that was an awful sight as people lay all over, half burned. Then we went over to Golden City. The Mond Nickle Co. from Sudbury sent up a Hospital train after the T&NO crews had fixed the roadbed where the ties had been burned out. I left Porcupine on July 12, 1911 about 3 p.m., working with the burned people on the Hospital train. there were some coaches, some boxcars and a lot of express cars and on the way to North Bay quite a few people died.

I went back to Porcupine and worked at carpentering and various jobs. The first World War came on and everyone was enlisting. I was turned down because of a silver plate in my knee where it had been split open by a skate. I was writing to a girl in North Bay who I thought a lot about when around there, Malvina LeBreche, and we decided to get married. We married on May 12, 1915 and went to live at South Porcupine.

We had two children, Eleanor was born the next spring and Eddie a year later. When Eddie was born my wife had a busted vien on the brain and went practically our of her mind. I was left with two small children. The LeBreche's at North Bay took Eleanor and I boarded Eddie with Mrs. O'Keefe at North Bay who raised him until he finished school. As soon as Eleanor got a little bigger I put her in the convent at Haileybury; she was there at the time of the Haileybury fire. Then I took her to the Cochrane Convent and she had fever the time of the epidemic. After that she went back to North Bay and went to the Convent there, later going to my sister Mrs. Gordon Beckett, at Toronto where she took two years of Business College.

After I was alone I worked for Dome for a while, then to Iroquoids Falls on railroad construction. Then I went with the Forestry Dept. on exploration (timber & water power). I went on two trips north from the CNR railroad to James Bay with a group of young foresters for two winters and one summer. I eventually got tired of these trips and went back to Dome Mines at Porcupine. In the spring of 1927 I left Dome and went to Red LAke, following the gold rush of 1926. I was on board the first plane out of Hudson after break up. Captain Stephenson, or Peg-Leg as the boys called him, was the pilot. He was later killed in a plane accident at Winnipeg and Stephenson Field was named after him.

Doug Wright from Dome, a geologist of renown (when he was sober), was living in a tent beside the lake shore. One day the manager from Dome, Mr, Defencier, (who wore a chin beard) was supposed to fly in. When the plane came over old Doug came out of the tent, one brace down, bare feet in mocassins, looked up at the plane and said "If that is not Old Diffy in that plane it must be Jesus Christ himself."

Bill Brown built a large building that he operated as a store and Post Office. Upstairs was a bunk house where you could sleep on the floor if you had your own eiderdown or blankets. He was married to a squaw, one of the best cooks I ever saw, but an awful woman to get drunk when she could get it. The Christmas of 1928 Bill was out to Winnipeg buying supplies for the store. Somehow Mrs. Brown got hold of a case of Benedictine on Christmas eve. She got drunk and sat on the case in the middle of the floor with a big butcher knife in one hand and a bottle in the other. Anyone who wanted a drink had to give her a kiss; you would be surprised how many men took a chance on that knife. By some select maneuvering the case was swiped and taken outside; that, and what was bought from the bootlegger, started things up and soon everyone wanted to fight. Myself and a clerk from the Hudson Bay Trading Post announced that we were putting on a show over the store. There were 50 or more men there and nearly everyone had a bottle. We made a big circle on the floor and anyone who wanted to fight had to get in the circle after we searched whem for knives and blackjacks. There were numerous bouts. A big half Indian, half French who was the Manager of the Hudson Bay and a Swede, Big Ole, fought for a half hour. We had gloves and made them put them on. I announced that I had a dark horse who would take on the winner and anyone else. The big Indian beat Ole and then I brought up Bill "Windy" McDonald from a room downstairs. He was a pretty smart boxer in those days; he did not drink and had done a lot of boxing in the ring around Cobalt, Porcupine and Cochrane. He only weighed around 165 while the Indian was around 200. We put the gloves on Bill and he played with that big Indian for a few minutes, then caught him one on the chin. He was out cold and they carried him over and put him on a cot. I never knew when he woke up as someone announced that another case had been produced in the living quarters at the back of the store. I went back to the cabin; if they wanted to kill someone I wasn't going to be mixed up in it. I did not take a drink nyself that night as I had to work Christmas Day. Bill Brown couldn't stand prosperity and he sold the store. He moved to West Narrows at the west end of the lake and raised his family on moose meat and fish. He drowned about 5 years later; some say that the old squaw pushed him off the dock when they were both very high on a batch of home brew.

There were some real characters in Red Lake, Joe Barron, the physical culture addict, who lived in a shack on Pipestone Bay used to run the 24 miles to Red Lake in the wintertine. When he got to Wolf Narrows, which were always open in the winter, he would take off his clothes and plunge in to cool off. He always took his bath in the snow during the winter and I always wondered if he dug down in the muskeg to get some frozen mud to lie in during the summer. Then there was Red Mautault who ran the moonshine circuit for a couple of years without the cops ever catching him. Ed Patterson and Emil Joyal used to stay in a cabin across from the Gov't. docks. Joyal went out on the dock early one morning to get a pail of water, being dry after a hard evening, and fell in the lake and drowned. Ed Patterson carried on alone and later died at Red Lake.

Old Oscar Bouchard used to work with us in the shop at Howey. I recall one time, after he had been off for a couple days making the rounds, he came over to the bench where I was working. As he cut some plug tobacco and rubbed it up to put in his pipe, he said, "Nels, the world is wrong". I asked him what was the matter this morning. "God made the world wrong", he repeated. "When a man gets old, God takes away his vitality and He should take the notion away too".

Another character was old Paddy Coyle. He had some very well off sisters out in B. C. After they found him through the RCMP, they wanted him to go out west. The police tried to get him to go but he would say, "And what do they want me out there for, I haven't seen them for 40 years. I'd be sitting around in a biled shirt, and if I was to slip away for a beer I'd be sinning, that's what I would. Tell them to send me some money. I want to build a cabin here, then they can come and see me." Well, the sisters did send Paddy $500 and I don't think he ever wrote to them. He lived across the bay in the old Red Lake Centre cookery. The roof leaked so he put his tent inside the building and lived on rabbits. He died there surrounded by a pile of rubbish and rabbit skeletons.

Tim Crowley was an old prospector who had some claims on McKenzie Island. One time he ordered a bale of hay and a bag of oats for his horse. These were shipped by Western Canada Airways from Bowman's store in Hudson and the freight bill came to $103. A few days later, when Tim was starting out for home, the plane was stuck in some slush on the lake and the pilot asked him to pull it out. After he did, the pilot said, "How much fo we owe you?" Tim replied "$103", and made the pilot receipt the freight bill.

Mike Bousan was from Newfoundland and he liked to boast that it had been 44 years since he came to Canada. It would make him mad when I would say, "And Newfoundland only two cable lengths away from the mainland". One time when I was going outside, I got a ride with him in his boat as far as Gold Pines. It was on in the evening when we arrived there, and, of course, we had to visit Fred McCammon's establishment to hoist a few before supper. I don't know whether we did get any supper that night or not. I had to wait until the next noon to get the boat to Hudson. After having a few eye-openers the next morning I got Mike to stand on the platform in front of Joe Kirk's store and took several pictures of him with a squaw and some papooses. I had them developed at North Bay and sent a couple back to Mike. I wrote on the back of one picture, "I am also sending a set of these to your wife in Haileybury". Later when I got back to Red Lake, and met Mike, he grabbed me by the neck (he had a hand as big as two average men) and said, "Did you send those pictures home?" Amid the gurgles and head shaking I finally convinced him that I hadn't.

(1) The family actually emigrated from Thornborough, Buckingham - probably through the port of Cardiff.

A TRAPPER'S TALE

Written in late 1952 by Nelson Spiers

Most of my life has been spent in the bush country of Northern Ontario, having roamed around from Quebec to Manitoba in various capacities - timber cruising, with forestry students, guiding and looking for the end of the rainbow (prospecting). I have sailed the Hudson Bay from Albany to Moose Factory in a freight canoe and I have been up and down the Abitibi River before the survey was made for the railroad from Cochrane to Moose Factory. I was working at Vipond Mines in Porcupine the day of the big fire, July 11, 1911.

After working and prospecting in most of the camps in the east, I came to Red Lake in the spring of 1927, on the first plane out of Hudson after breakup. It was an old Jenny piled high with freight and mail. Captain Stephenson, the pilot, was later killed in an accident at Winnipeg. Red Lake was frontier in those days, one log building and a bunch of tents. After staking a few claims I went to work at the Howey Mine. The following winter I was trapping on the Bloodvein River. In those days there were no allotted areas, or no licences. Black and silver fox were plentiful and beaver were worth more than they are today. Fisher were tops for prices. Some years later I took up a line south and west of Upper Medicine Stone Lake, and have held it ever since.

There were few beaver in this area at that time but, by farming them over a period of years, I now have between 40 and 50 families. Although the Dept. of Lands and Forests now allow me a large quota, I have never taken more than 25 in any one season. Possibly I should have taken more; this summer I have seen empty houses where the feed had not been eaten last winter. Possible the plague or some disease that is spreading has killed the beavers off. I will know later in the season if I find any diseased animals when I am trapping.

My main camp is now near the west end of my territory with two sleep-out camps south and east. As I am getting along in years and have no dog team at present, eight miles is a good day's travel in the short days of fall, with the work one has to do along the line setting and tending traps. For fisher I use deadfalls which take a little time to build. Once set there are no traps to freeze down or get snowed in, and they take little attention if set in localities where there are few squirrels.

This was a very bad fall to travel. It froze enough early in October to seal up the narrows and small bays, and we could not use the canoe to get around. Then it turned mild, although not enough to clear the ice that had formed. The larger lakes did not freeze over until late in November and it was the 27th of November before I could cross them. I came in by plane on October 26th, and after an awful lot of hard work on account of ice and open water, I managed to get some supplies and new stove pipes down to the other camp.

Every time I think of stove pipes it brings back memories of one time I was employed by the forestry department of a large pulp company in Eastern Ontario south of Abitibi Lake. It was a very late freeze-up and impossible to get across the lake to the C.N.R. line at Low Bush. There were reports to get out to head office and as to go across country to the railroad at Matheson would take a good two-day hike, about 40 miles, I decided to start out early in the morning. I knew if I could make the Ghost River at a certain point, I would not have to sleep out. Louie Ramoe, an old trapper, had a cabin there. I made the Ghost just before dark and Louie was at home. I had been cautioned to use a lot of diplomacy if I did get that far as Louie did not like anyone around. I told him who I was and that I was on the way to Matheson, that I had my own grub, and would like to stay there that night as I was not packing a bed roll. He said to come in and as soon as I stepped inside the cabin I noticed that he had his stove set up high on a frame, with 3 steps going up to put wood in and to do the cooking. I said to myself, "He must be bushed for sure". I was tired and we didn't talk very much that night but as I was leaving in the morning I said to Louie, "Why have you set your stove up on that frame?" He replied, "Wot in 'ell would you do if you only had three stove pipes?' The others had all rusted out so he wasn't so loony after all.

Well, back to the trap line. I am not bothering with beaver the first part of the season for they have lots of feed of their own and are slow to take bait. Beaver trapping is faster after Christmas. I put out a line of mink traps and dead falls for fisher, and on the first trip around I had a couple of mink and one nice fisher, also a dozen ermine. On the next trip I had two more fisher and since I only have a quota of two, I had to spring the rest of the deadfalls.

It was November 25, and the moose season was open. Eating salt pork and fish for a month gets kind of stale so I decided to get me a moose and have some fresh meat. I had seen several moose since I came in along the line. but after having hunted four days I was still not lucky enough to get one. One day I startled three and by the direction they started off I knew about where they would cross. I circled back around and was sitting on a log waiting, when I saw something coming down the draw, knocking the snow off the underbrush, and out walked two nice Red Deer. All at once I could taste venison. "Well, deer season closed yesterday," I said regretfully and made myself go home and fry some more fish for supper.

You hear people saying it must be an easy life trapping. Let me tell you it is one of the hardest ways to make a little money. When you come out, the buyers beat you down to about half what you should get. You are out in the cold and it may be blowing a gale on some lake that you have to cross to get to a cabin that you have not been to for a couple of weeks. First you have to get a fire going, then either melt ice or spend half an hour cutting a hole to get a little water. Maybe you were in a hurry last time and there is not much wood cut, so it's a case of taking the old Swede saw and going to work.

Usually in the short days of November and December it's dark, so you light the kerosene lamp. If you were lucky along the line with your traps, you have fur that has to be hung up to dry and thaw out before skinning. Beaver, otter, fisher, lynx, and fox have to be skinned, as they are too heavy to pack along. Mink, ermine and that trap pest, the squirrel, can be carried along to the main camp. Oh, yes, it's a real pleasure, especially if you get into slush on the lake. Recently I built two fires in one day to melt the slush off my snowshoes. After a trip around the line and you are back in the main camp, there is always lots of work to do. Usually our stoves are small, and baking bread is quite a problem. There are beans to boil and bake and after baking beans I turn them out in a flat pan to freeze. One can thus carry enough for a week. Usually at sleep-out camps there is tea, sugar, dehydrated potatoes, oatmeal, dry milk, dry fruit and of course before November 25 (when moose season opens), the old standby, salt pork.

In my long association with the wild animals in the bush, as friend and foe, I have often been able to see the mothers rearing and teaching their young before starting them out on their own. I have watched the otter playing and sliding down the banks or the mother beaver and her kittens out on the house in the evening sun. This summer I saw a cow moose swimming out to an island with her two calves, and on shore a big black bear. He was after one or both of those calves as they were only about a week old. Personally I think there should be a bounty on bears the same as wolves as they destroy a lot of moose calves. They don't bother the deer fawns unless they see them, as a young fawn has no scent whereas moose calves have. They also destroy a lot of beaver by tearing a hole in the houses and getting the kittens. I used to think that it was wolves that tore the beaver houses open, until one spring I was rat trapping. While paddling along I saw a big black bear working on a house. You can rest assured that was the last beaver house he tore apart.

It may be a hard life but I still love the nice clean air, the scent of the pines and the great solitude.

* * * * *